Apart from when I was carried as a baby, I had begun going to the Main Street area of Greensburg with my mother in the early 1950s. Usually my father would drive us. Occasionally we walked around as a family. One time I recall was an unusual event—a huge “Old-Fashioned Bargain Days” celebration. Stores were charging early 20th century prices. I remember sawdust on the floors of Murphy’s five and ten, and wood planks on the sidewalks, with the trolley tracks still visible on Main Street. Also there were hundreds of people milling around—more than I would ever see again at one time in the downtown.

But most times, my father would go back to work while my mother took us shopping. Sometimes it might be just my mother and me, if we had to get some specific items of clothing for me, like a suit or shoes.

|

| S. Main St. with trolley. On right the red facade of Murphy's 5&10 next to Craig Shoes |

When we weren’t driven, we went to town by bus. That’s when

we’d moved to South Lincoln Avenue. Though Greensburg and western Pennsylvania

were among the first to adopt electric streetcar systems in the late 19th

century, trolleys within Greensburg began fading away in the 1930s. City buses

began taking over some routes immediately.

A few streetcars, including one from Greensburg to Youngwood, lasted

until 1952. But buses were the main

public transportation in Greensburg.

Our bus was the Hamilton-Stanton, which ran two or three times an hour. We—my mother, my sister Kathy and I—might walk down West Newton Road towards the corner of Hamilton Avenue and West Newton Street to catch it.

|

| Greensburg buses looked like this standard GM bus of the 1950s |

There were times my mother went to town by herself, and I recall being posted at the picture window to see when the bus made this turn, so she could then hurry down to meet it coming back.

My mother shopped for the family at the Main Street department stores: Troutmans, the Bon-Ton, and occasionally the more expensive Royers, as well as the five and tens (Murphys and McCrorys), Joe Workman’s, Sears, Penney’s and the many small shops, especially shoe stores. I liked the Bon Ton neon sign hanging out from the structure, with a clock in one “O” and a temperature gauge in the other. And Royers had those pneumatic tubes that sent metal capsules with sales slips zipping up and across the ceiling to wherever.

We might stop to eat at one of the small lunch places, some with their entrances below street level, such as the Chat & Chew, or a drug store soda fountain counter or the counters at the five and tens. We might also visit the carpeted interior of the Singers (Sewing Machine Co.) store, in the years my father worked there, before going into the Penney’s next door.

Later I would walk into town, alone or with friends. We would start down the tree-lined West Newton Road (before it was relocated to feed into the east-west bypass highway), past the sign marking the Greensburg city limits, then past Beehner’s Garage, which was a gas station and the local dealership for American Motors Hudson, Nash and Rambler cars—and where I got my free autographed photo of Fess Parker as Davy Crockett (“When you’re out to win, try the Crockett grin.”)

Then we would cross Hamilton and walk up the leafy sloping West Newton Street, past Paul’s Pharmacy (where I was sometimes sent to get medicines, though they also delivered), to the V at the crest of the hill where West Newton met Pittsburgh Street, and the old mansions started (by then relegated to being insurance company headquarters and funeral parlors) as the street plunged downward.

|

| Pittsburgh St. looking towards downtown. House on left with columns (green then) was Aunt Pearl's. |

It evened out a bit at Aunt Pearl’s house, next to Butz Music Store, where I’d briefly taken clarinet and later a few guitar lessons, before it sloped steeply up to Pennsylvania Avenue, with Main Street at the next crest, one short block farther. (Aunt Pearl was the former Prosperina Iezzi of Manoppello, my grandmother Gioconda's younger sister.)

We didn’t usually make the right turn to the southern part of Pennsylvania Ave, except to go to the Post Office at the end of the Pennsylvania Avenue business district, a grand old Beaux Arts building with impressive columns, and a long history. Designed as a twin to the Charlottesville, Virginia post office, it opened in 1911—just in time for onlookers to stand on its steps to watch one of the last Buffalo Bill Wild West Shows parade through Greensburg.

|

| Greensburg Post Office around 1950 |

In 1965, a new and smaller post office was built across the street, and the old Post Office building became the new public library. But when I needed stamps in the 1950s (when First Class cost 3 cents), I entered its hushed official recesses.

I had an active relationship with the U.S. Mail, thanks partly to Boy’s Life magazine, which revealed exciting stuff you could get sent to you—like color photos of train engines—just by writing and asking for them, which I did. Then there were all the toys I sent for with cereal boxtops and maybe a dime or a quarter (plastic frogmen that bobbed in the bath if you put baking soda in their feet) or the inner seal of a jar of Ovaltine (various Captain Midnight devices, including the signet ring and the famous decoder badge.)Then later, in high school, I might head down this way to the new Greensburg Photo Supply. But most of the time, if my friends and I didn’t continue directly up to Main Street, we turned left on the corner of Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania at Thomas Drugs (which held this spot for more than a century) and we headed north—the shortest route to the movie theatres.

|

| Manos Theatre when it opened 1930 |

The Manos was a large, ornate but musty old movie palace that to us looked immense, like something out of the movies itself. When I first started going, it even had a few ushers in faded uniforms. I recall looking around at the building as I anxiously waited for the show to start—at the mysterious cornices and phantom balconies, the peeling paint on the distant ceiling, the heavy, dusty drapes.

The Manos eventually became the Palace Theatre, hosting live

performances only. Much of the interior

has been restored, including some of the elaborate murals that were hidden

behind the grime of decades, yet even back then something suggested there was

more to this theatre than met the eye.

Even in its 1950s faded glory, it was the biggest, most ornate public

space in town that we knew, except for the Court House, which was pretty much

off limits. And at some point in the

50s, it was air-conditioned, a real rarity in those hot summers.

The Manos eventually became the Palace Theatre, hosting live

performances only. Much of the interior

has been restored, including some of the elaborate murals that were hidden

behind the grime of decades, yet even back then something suggested there was

more to this theatre than met the eye.

Even in its 1950s faded glory, it was the biggest, most ornate public

space in town that we knew, except for the Court House, which was pretty much

off limits. And at some point in the

50s, it was air-conditioned, a real rarity in those hot summers.

At the Saturday matinees we saw all the new science fiction and “bug-eyed monster” movies (The Creature From the Black Lagoon, This Island Earth, War of the Worlds, It Came From Outer Space, Forbidden Planet etc.), the newest westerns and some of the comedies, plus older adventure classics. Even though these matinees catered to the throngs of a baby boomer audience, they linked us to previous generations who attended similar Saturday matinees in the 1940s and 1930s. But by the 1980s and the malls and multiplexes on the highway, this link was broken.

|

| restored Manos/Palace as we never saw it |

Then at some point, probably not until the 1960s, when the Strand closed for repairs, the Grand was refurbished and suddenly reopened. It lasted into the 1970s, as the downtown deteriorated after the shopping malls arrived, and it started showing raunchy movies before it closed forever.

|

| ticket booth etc. exactly as we saw it |

The Saturday matinees cost 25 cents, the usual admission for children. We lined up to buy a ticket at the marble booth outside, under the marquee and at the front of the outside lobby with its black and white checked stone floor.

Photos from the movies being shown or coming attractions were on the walls out there, as well as in the long inside lobby. We walked through multiple heavy glass and metal doors and up the gently sloping, long tiled indoor space. Then another set of glass and metal doors, with curtains over all of them except the one at the far right. There the ticket-taker stood or half-sat on a stool. Past those doors was the carpeted and darkened inner lobby, with the bright concessions stand dead center ahead.

With a mirror behind it, where the big popcorn machine popped away, the concession stand itself was a long glass counter over a display case. Inside, arrayed by price, were the available treats.

If I’d been given 35 cents, I had to choose how to spend that extra ten cents to fortify myself for several hours. There were items that themselves cost a dime, and popcorn was 15 cents. But there were nickel boxes of candies: Good & Plenty, Dots, Jujy Fruits, root beer barrels, Spearmint Leaves, Black Crows, Chuckles and more. Not boxed but often a nickel included a Turkish Taffy (vanilla and chocolate), varieties of licorice, bag of M& Ms, and rolls of Tootsie Rolls and Necco Wafers. Two nickel boxes, spaced over time, often seemed the right choice. |

| steps from lobby with wedding model in restored Palace |

There were dark maroon curtains pulled back from the entrances to the theatre auditorium itself on both sides of the concession stand. Across this inner lobby to the left of the stand was a set of wide, carpeted marble stairs. They led first to the largest men’s room I’d ever seen, with lots of marble and mirrors, and also to the balcony, which was often closed with a “velvet” rope and a sign, but not always. On the landing there were vending machines, one of which had boxes of some of the same candies as the concession stand, but with an additional choice: a window covered with cardboard and the words “Take A Chance.” Since I figured it was just another box of candy, and might be one I didn’t like such as the Boston Baked Beans, I don’t think I ever did. Maybe once.

If I started out with 50 cents, then popcorn could be on the menu, or maybe a walk up to Isaly’s for an ice cream cone after the show. There was a water fountain outside the men’s room so I was not tempted to buy what we called “pop.”

When I was a bit older—perhaps after I had a paper route--I discovered the restaurant in the nearby Greensburger hotel where I could get a hamburger, fries and a coke for a total of 55 cents. That briefly became an after the movies destination.

My other major destination in town was the public library, when it was on South Main Street, taking up the former home of the prominent Greensburg citizen, Richard Coulter. This Richard Coulter had been a General in World War I. His family was wealthy from banking and coal, and he donated his old home for the library. It opened in June 1940. Built in 1881, this brick building may have previously been the home of his father, the first Richard Coulter, who was a Member of Congress and a state supreme court judge. (The library has moved but the building remains.)My mother took me there to get my library card. The librarian explained the rules: I could take out no more than three books at a time from the children’s room, for two weeks, renewable for two more weeks. The overdue fine was on the order of a penny or two a day.

I took my first book out that day: a novel entitled The Space Ship Under the Apple Tree, a kind of precursor to E.T., by Louis Slobodkin. It was a little over my head and I didn’t finish it within the two weeks, but I soon was walking to and from the library on my own, taking out all manner of books, including volumes in the Winston Science Fiction series for young readers, and Robert Heinlein’s science fiction novels for that same readership. (Heinlein had stories in Boy’s Life so I knew about him.)

By fifth grade I was heavily into the Hardy Boys. I read novels about sports by Joe Archibald and John R. Tunis, as well as biographies of sports figures like Jackie Robinson. Inspired in part by a couple of service academy television shows (West Point Story and Men of Annapolis), I took out Midshipman Lee of the Naval Academy and similar books.But there were also plenty of times that my neighborhood friends and I walked to town with little or no purpose at all. For a couple of years, we might immediately go into Murphy’s five and ten and down the stairs to the first floor (or basement), and look at the model airplane kits. These were boxes of plastic parts you glued together with “airplane glue,” carefully affixed the decals (which we called “deckels”)and attached the plane to a plastic stand. The kits cost 98 cents, which with tax came to $1.01. That was pricey for us, so I had just three planes that I remember: a dark red Messerschmitt ME-109 from World War II, which I probably bought just for the color; a silver F-100 Super Sabre jet and a black fighter jet, possibly the Navy Panther. I think I also had an intricate silver model of a helicopter.

Later, when I started buying 45 rpm records, I often bought them in Murphy’s basement. For awhile there was an actual record store on Pittsburgh Street, across from the Court House and the county jail with its steeple-topped tower, where I met and got the autograph of Conway Twitty, who had a hit record with "It's Only Make Believe." Not my biggest thrill.

There were other toys and sporting equipment to interest us in Murphy’s basement, but our forays into town weren’t much about shopping. We would take the elevator in Troutman’s department store just to ride it, at least until the operator stopped cooperating. Or we might race up and down the back stairs from floor to floor.

Troutman’s was as it had been for decades, the largest department store in Greensburg, though the Bon-Ton gave it competition for awhile. There were six floors of merchandise (the Bon-Ton had five), and its own restaurant. It remodeled and added an annex across the side street (Second Street) behind Bon-Ton in 1955, celebrating its opening with an appearance by Vaughn Monroe, a popular singer in the 50s, originally from Jeannette. (As a child I thought I could imitate his style, mostly by keeping my tongue in the back of my mouth.) Troutman’s got the first escalator in town in 1958, and would expand down to Pennsylvania Avenue in the 60s. In the 50s it was always busy, so it drew us like a magnet for mischief.After our wanderings we might end up at a soda fountain for vanilla cokes, or a booth at Thrift Drugs, where we might rig the salt shaker to invisibly dispense pepper. Several places had ice cream sundaes and milk shakes. Isaly’s had the skyscraper cones and their Klondike bars for a dime, but for a good nickel ice cream cone there was the Silvis Diary store a half block east of South Main.

Our mischief-making was somewhat tempered by Greensburg being a small town full of relatives and parental acquaintances. At one time or another, for instance, my Aunt Carmella worked at Hoffman Drugs on North Main, and my Aunt Rella was behind the sandwich counter at Thrift Drugs on South Main.

But there was plenty of legal amusement. Sometimes McCroy’s five and ten had a contest in which you picked a balloon hanging over the sandwich counter which the waitress pricked with a pin, and read the price on the paper inside, and that was the price you paid for a banana split, the most expensive ice cream concoction. It was never more than the usual 35 cents, but it could be less—less even than the 25 cent sundae or milkshake.

At first South Main Street pretty much ended for us at the library. But a block or so beyond it was the large, long brick building that had been the West Penn Railway trolley headquarters since 1927. By the time I was walking that far down, the trolleys were gone (though for awhile the tracks were still embedded in Main Street and other downtown streets) and the building housed City Hall (pretty small at the time) and at the other (western) end, the bus station. Apart from city buses, there were buses to other nearby towns (like Youngwood) and to Pittsburgh, and Greyhound buses that went everywhere. The bus station may have been quite large, including a restaurant, but I mostly recall the nondescript waiting room from as late as the late 1960s. |

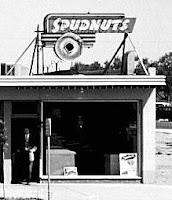

| a generic Spudnuts from the 50s |

But in the 1950s I was most impressed by another feature there. I’d read in the Readers Digest about this amazing new kind of donut called the Spudnut, which would be sold exclusively in a chain of stores across the country. I was thrilled when one of them opened right there at the bus station.

A little further south on Main was a large vacant lot that briefly became a baseball field. After tryouts for Little League baseball that seemed to attract every Baby Boomer boy in the Greensburg area, those of us who didn’t make one of the proper teams were exiled here in a Minor League. We didn’t get uniforms, just caps. The teams were named Vampires, Zombies, Ghouls etc. My team was appropriately the Ghosts. I remember hot afternoons exiled in the outfield, watching occasional balls hitting stones and weeds on the sloping field as they made their meandering way towards me.

This lot wasn’t vacant for long. Reputed to be the site of Greensburg’s public hangings, it soon hosted the town’s first strip shopping center.

Back up South Main Street, past Troutmans, the Bon Ton, McCrory’s, Joe Workmans and Royers and across Pittsburgh Street was the immense and ornate gray Westmoreland County Courthouse. We didn’t have much to do with this building as kids, except for a couple of things that don’t exist anymore: the public water fountain spilling into a round silver dish out in front (paid for, it said on its stone base, by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union), and down a set of stone steps: the ample public restrooms.As for North Main, we hardly ventured up the hill past the Sears store. Also on this block was Lee’s Restaurant, where my mother had frequently dined, she told me. It was a fashionable place for some decades. I didn’t discover it myself until its last days when I returned in the late 1970s. I usually sat on a stool at the counter and drank coffee in the afternoon, always tempted by the excellent coconut and chocolate cream pies. But the tables still were covered in thinning tablecloths, with real cloth napkins, though in delicate condition: testaments to the standards of its fading past.

|

| photo from 50s of Cathedral School students running for their buses, with Greensburg High across the street. |

|

| old St. Benedict, then Cathedral School, now Aquinas Academy |

|

| The YMCA on Maple Ave. |

Also down this way, at 15 East Otterman was Vince Di Pasquale’s tailor shop (listed in the Greensburg Directory in 1959), and at 24 E. Pittsburgh Street, Rocco Mazzaferro’s tailor shop (listed 1951), both long-time friends of my grandparents Ignazio and Gioconda Severini.

|

| Greensburg train station grand entry |

We were warned against this corner cigar store as a disreputable place, so it wouldn’t be until the early 1960s that I ventured inside for long, to search those paperback book racks. It also had a long row of dark wood phone booths along its western wall near a side entrance, opposite the Rialto bar, which at the time may still have been a venue for gambling, especially “the numbers.” Those phone booths might also have been involved. (The Rialto bar may have gotten its name from the Rialto Theatre, which was replaced by the Manos.)

Down Otterman past another newsstand, Greensburg News (where in later years I bought the Sunday New York Times, as did the man who wrote mysteries about Rocksburg under the name of K.C. Constantine), then to the right was Harrison Avenue. The row of buildings on that narrow street where the tailor shop that had once employed Ignazio Severini was still there, though the tailor shop was not.

The only business in that row that interested us was the Greensburg radio station WHJB (620 on your radio dial.) For some years there was a display window behind which the announcer then on the air could be seen from the sidewalk.

When I was in 6th grade, I had a radio in my room on the bookshelf above the old desk I’d inherited, next to my globe. My father had put it together from a kit. It was supposed to be a short wave radio but the only station it reliably got was WHJB in Greensburg. I often listened to the WHJB “Night Watch” music program while I did my homework. I listened to it on the ominous night that the country got a shock when Russia launched the first human-made satellite, Sputnik 1 in 1957.My other memory of WHJB is also from the 1950s: a commercial for a shop on South Main Street called Nancy’s, which had an orange facade over its entrance. Frank Sinatra had a hit in the mid 1940s with the song “Nancy (With the Laughing Face.)” The commercial parodied that line from the song, with several men singing off-key, “That’s Nancy’s, with the orange face.” I remember as well that it was WHJB that broadcast the news of the fire on Main Street that gutted Nancy’s.

At the end of Harrison, past the stately Penn Albert Hotel on the right, was the Greensburg train station. This impressive brick station with stone trim and a tall clock tower decorated with copper was built in 1910 to 1911.

This particular corner of Greensburg was practically unchanged from the 1940s or even earlier, except that the station was closed and partly boarded up. I can vaguely remember a visit inside the station when it was open—the waiting room with its dark wooden seats, and attendants pushing carts to the adjacent freight office. In the late 1970s it would be listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and even later, part of the inside would be restored for a series of bars and restaurants, but in the mid to 1950s it was beginning its decades as a ghostly, slowly deteriorating and beautiful phantom of the past.

However, the cement tunnel between what had been the waiting room and the baggage building that led to the tracks above was still open and functioning in the 50s. Up either of the two sets of cement stairs, there were two brick islands across from each other, with two sets of tracks running parallel between them, one eastbound, one westbound. On the other side of each island was another single set of tracks, usually reserved for freight trains.

These brick islands were still used by people waiting for passenger trains. It was not yet the era of Amtrak, so these were still Pennsylvania Railroad and B & O Railroad passenger trains that stopped here, going east and west. (In 1958 or so, I would take my first train from here, to Chicago, on a reward trip with other paperboys for the Greensburg Tribune-Review.)

Along these islands there would usually be a few large wooden baggage carts on wheels with high platforms, up against a steel column supporting the open-air roof. We discovered that if we climbed onto a cart, there was nobody to make us get off.

|

| In this fairly recent photo of a special train visit, the old brick platform can be glimpsed in the foreground left. The tracks that were on the outside of the platform are gone. |

We then might spend hours sitting or sprawled on the cart waiting for trains to come through. Most of the time it was quiet, but often enough we would spot a train in the distance. If it wasn’t stopping, sometimes the train didn’t even slow down but blew through the station as though it wasn’t there. This caused a windy roar that had us clutching onto the cart frame and the column. And then it was gone, until the next one.

Once, while our attention was fixed on the train rushing through in front of us, another train ran past behind us on the other side. We were in a speeding train sandwich—double the thrills!

One summer when my Aunt Toni was visiting from Maryland, my cousin Dick Wheatley accompanied us on one of our forays into town, ending up at the train tracks. He remembered that people gathered on the platform to board a passenger train, including the Mayor of Greensburg, who told us to take care of the town while he was gone.

No comments:

Post a Comment