|

| Italian passenger ship S.S. America |

Ignazio soon got a job in a large tailor shop in Greensburg near the train station, on Harrison Avenue. This was probably the shop opened by Anthony Robert in 1914. But over the next two years the news from Manoppello was not good. His parents’ health grew worse. First his mother died, then a year later, his father.

Even the news about Italy was bad. With continued poverty there was political unrest and violence. The new Fascist party and its armed thugs, the Blackshirts, began a campaign of strike-breaking and attacking socialist politicians. In late 1921 Benito Mussolini renamed them the National Fascist Party, and in the fall of 1922, Mussolini organized a march on Rome to demand power. To avoid bloodshed, the King made him prime minister. It was the beginning of terror, warfare and the Fascist dictatorship.

By then Ignazio and G had already decided she would join him in Greensburg, and they would remain there.

|

| On her 1976 visit to Manoppello, Gioconda with her sisters: Serafina, Suor Carla, G., Onorina, Stella; with Rose Severini. |

Another factor in Ignazio and G’s decision could have been the new United States laws to limit immigration, specifically from Italy and Eastern Europe. (Immigration from Asia had been almost totally banned for years.) The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 would become the sweeping Immigration Act of 1924. The 1921 Act continued to allow close relatives of U.S. residents to join them, provided they were either spouses or would vouch for their support. But there was no guarantee that this provision would remain.

Gioconda might have gone as early as 1921, when her youngest sister, the 19 year old Prosperina, sailed for America and headed to Greensburg, where she was to marry the 32 year old Joseph Romasco, originally from Manoppello. Instead G. waited until Flora was a little older. Just a month after Flora’s second birthday, they took the train to Napoli to begin their journey to America.

Gioconda was traveling with her cousin Giuseppina, also a Iezzi, who was also married to a Severini, Ignazio’s cousin Raffaele. Raffaele Severini lived in Newark, New Jersey. Guiseppina also had a daughter with her, Antoinetta, who was eight years old.

Before they could get on the ship, they were herded into a building with more people than she had ever seen in one place, G. remembered. Doctors examined them and they were dusted with powder for lice. The officials were not mean but most of them showed no feeling but impatience. The people were scared and so tried not to offend the officials who would decide if they were allowed to board the ship. Some travelers would get no farther than this: if they were found to be too sick, or for reasons that remained mysterious, they were turned away. They were careful, because if the officials in New York sent them back, the steamship company would have to pay the fare.But G and Guiseppina and their children were allowed to board. It was a big steamship with two smokestacks. It was called America.

There were many steamships called America over the years, from several different countries. This S.S. America was an Italian ship built in 1908 that made its maiden voyage from Genoa to New York in May 1909. It’s the same ship that brought Ignazio’s sister Anna Severini to America in 1914, also from Napoli. It continued taking passengers from Europe to New York, including returning American soldiers after World War I. Just two years after this 1922 crossing, the ship changed destinations to South America, and four years after that it was scrapped.More generally, G’s voyage in 1922 was very near to the end of an era that had begun at least thirty years before. With the restrictions of the 1924 law, the ships full of immigrants soon stopped crossing the Atlantic.

But now safely aboard and with one worry behind her, G. faced the voyage itself. They were deep in the belly of the huge ship, and there were so many people. The only light came through the tiny windows, but she did not like to look out, because the water was right there, and it seemed it would cover them over at any moment. G. did not trust the food, nor some of the people around them. But Guiseppina helped with the baby, and Antoinetta played with her.

Once on the nearly two week voyage G. wrapped Flora in a blanket and took her on deck to see the sky. But the next day Flora was sick, and so there was another worry. What if they didn’t let her into the country because her daughter was too sick?Then they arrived in New York Harbor, on November 1, 1922: The Feast of All Saints. Some had gone on deck to see the Statue of Liberty. Then they approached their destination: Ellis Island.

They all were herded off the ship and into even bigger buildings than in Napoli, as big as cathedrals. There were many more people there, all talking different languages.

But again she was worried because some said the boat had arrived early. And when she got to the official who looked at her papers, no one was waiting. She had seen Guiseppina and Antoinetta ahead of them in another line, and her husband Raffaele Severini standing with them. He lived in a city nearby, and could come to Ellis Island every day to see if her ship was arriving.

She watched the official carefully. As he looked at her papers he frowned. He was not going to let her in. She did not know why.

Then another official came. He spoke Italian. He told the first official that her husband was here. Without him, she would be turned away. She thought it was a miracle.

But Ignazio was still in Greensburg. The man ready to sign for her was Raffaele Severini, Guiseppina’s husband. The first official looked at his identification, with the same last name as hers. He passed them through. They had landed in America.

G. and Flora went to Newark with her cousin’s family, to send Ignazio a telegram saying she had arrived. G. learned that it had been Guiseppina’s idea that Raffaele pose as her husband. There were so many people in so many lines that he was able to sign as the husband of two women. Besides, to them, all Italians looked alike.

Ignazio arrived in Newark the next day, looking very handsome in his new raincoat, tailored suit and his beret. But Flora would not let him touch her mother. She screamed at him in the Italian of Manoppello: “Get away from my mother! Don’t stand so close to my mother! I don’t want to see you here, you frog face!” This was a story G. told.

|

| Harrison Ave. Greensburg |

By American standards, Greensburg was an old town. There is evidence of Native Americans living in the area for thousands of years. The Lenni Lenape (Delaware), the most prominent in this part of western Pennsylvania when Europeans first arrived, were relative newcomers. The town itself was settled by these European transplants before the American Revolution, a place of inns and taverns a day’s ride on horseback from Ligonier to the east and Pittsburgh to the west. The young George Washington made that ride, and helped establish that road.

Incorporated just after the Revolution and named after one of its generals, Nathaniel Greene, Greensburg became the county seat for Westmoreland County, the last county established by the British government in the United States. There had been a regular stagecoach stop just across the street from where the train station was now. A hotel was built there before the Civil War, and a hotel was still there in 1922, the Lincoln Hotel.

The town, and especially this part of the downtown, was still growing. Much of that was due to the railroad. The Pennsylvania Railroad carved out its roadbed and started service in 1852. Soon it was linked to the rest of the state, and then the rest of the country. Hauling freight, carrying away the region’s coal and coke, and bringing passengers, the railroad still dominated in 1922. It was in that year that hundreds of people lined the Greensburg tracks to watch the latest demonstration of the railroad’s power: the largest train of locomotives to travel across the United States, a total of fifty steam engines. As Ignazio and his family got off the train at the large and ornate Greensburg station, opened just ten years before, they likely could see just outside of it on Harrison Avenue, across the way from the Lincoln Hotel, a much larger hotel under construction, the Penn Albert. It would be eleven floors tall, and after it opened in 1923 it would be a center for community events and entertainment, with its meeting rooms, the Crystal Room ballroom and Chrome Room restaurant, and the Roof Garden for music, dancing and big events. Many years later, one of those events would be the wedding reception of their son.And these were not the only hotels nearby. There was the Hotel Rappe about a block away—it was almost as large as the Penn Albert—the old Cope Hotel, and soon there would be the Keystone Hotel. |

| Hotel Rappe, later Greens- burger & General Greene |

The house on Hamilton Avenue where they were first to live was on the western side of Greensburg, near the crest of a hill and a corner of Pittsburgh Street, a major road to downtown. G. must have been pleased to learn that St. Anthony’s, a Catholic Church that served mostly the Italian community, was a short walk away.

Ignazio, Gioconda and Flora lived there with Ignazio’s sister and her family for about a year. Their second child was born in Greensburg, on July 28, 1923. She was baptized Antoinette Marie Severini. Shortly after her birth, the family moved to a house on nearby Vannear Avenue, which was close to the Westmoreland Hospital on Pittsburgh Street.

Though they were in a new country with a new language to learn, and they faced the possibility of some hostility and prejudice against immigrants and Italians, they were also surrounded by relatives and friends, and generally people from Manoppello who spoke the same language, the same dialect, with each other. There were also Italian clubs and lodges organized for social events, education and mutual support, and their numbers were growing.

|

| Picnic 1957 of lifelong friends: Carmen DePaul, G., Mrs Armelia De Paul, Vince Di Pasquale, Mary Di Pasquale. Ignazio taking the photo. |

Besides Vince Di Pasquale and his wife Mary, they remained close for years to several other families including Carmen and Armelia DePaul, and Rocco and Chiarina (Clara) Mazzaferro.

Armelia De Paul was born in Manoppello, and her maiden name was Gloria—the same last name as Ignazio Severini’s mother—so there was likely a blood relationship. She was born in 1896, and arrived in the U.S. in February 1924. Carmen--originally Carmine DiPaolo-- came from Polla in southwest Italy in 1913.

Rocco Mazzaferro was born in Manoppello in 1893, and arrived in Greensburg in 1910. Chiarina (Clara) Mariani came from Manoppello in 1919, aboard the Dante Alighieri. They married and had a daughter in 1934, Angelina, who would often be in the Severini home. Gioconda Severini may have been her godmother. Rocco was a tailor who eventually had a shop on Otterman Street in Greensburg.

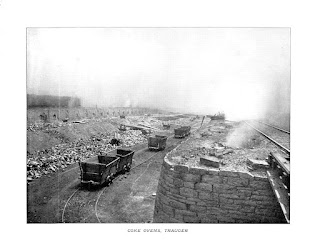

The Severini family was probably still living on Vannear Avenue when G.’s father Carlo Iezzi suddenly appeared. He stayed with them while he opened a shoemaker shop in a little village nearby called Red Dog (probably the village of Edna in Hempfield Township), where there was a coal mine. Many Italians lived there. It was called Red Dog because its streets were paved with the crushed stones that came out of the fires the miners made to purify the coal. The stones were pink and black and red. They were used to pave other roads, and even to make bocce ball courts.

One day in 1927 Carlo returned and said that he had sold his shop and had lots of money, and he wanted to take Antoinette to the movies. She was four. But G. didn’t trust his drinking. So he went out alone and didn’t come home that night, or the next.

Then Ignazio read in the paper that a man named Charlie Nezzi had been found badly injured on the railroad tracks under one of the bridges in Greensburg—the Main Street or Maple Avenue bridges. He thought it might be Carlo and called the hospital.The hospital said that the man had died. Another man had been with him, but they didn’t know if Carlo fell from the railroad bridge, jumped or was pushed. They knew he had been drinking. He had lived for a while after he’d been brought in, but no one could understand him, to find out where he lived. Sometimes he spoke English, sometimes Italian, sometimes French. Carlo had been back and forth to Quebec, and some of his friends called him Frenchy.

Natz told G., and she called her sister Prosperina, who lived in Greensburg. She was married to Giuseppe—now Joseph—Romasco. They had three girls: Mary (1922), Jenny (1924) and Stella (1926). They would have a boy, Louis, in 1929, and another daughter, Joann, in 1931. Prosperina called herself Pearl now, but G. continued to use her Italian name.

G. wanted Prosperina to go with her to the hospital, to identify their father’s body. Prosperina refused until G. got angry, and finally she agreed. They went together but when it came time to go down to the morgue, G. had to go alone.

They went down flights of stairs to the hospital’s basement. G. was taken to a body that was under a white sheet, with one arm dangling down. She knew immediately it was Carlo. She knew it was her father’s hand.But the doctor and another man there insisted she could not identify him officially unless she looked at his face. Finally she allowed them to pull back the sheet. The next thing she knew she was sitting on the floor, with the doctor looking at her as the other man held her up. She had passed out and swallowed her tongue.

Despite the uncertainty about how he died, Carlo Iezzi was buried in the Catholic Cemetery in Greensburg.

In 1928 Ignazio Severini was able to buy a small house at 637 Stone Street, not far away on the western side of Greensburg, with a $100 down payment. It was valued at $3,000.

Stone Street was a short, quiet street of houses. Across a large field was Grove Street, which shortly intersected with Hamilton Avenue, but this was some distance south from where they had first lived with Ignazio’s sister. At Grove and Hamilton, looking west just beyond the new Sacred Heart School (it opened in 1922), there was a creek and a steep hill with nothing on it but dandelions and trees. It was where the city of Greensburg ended. G. would take Flora and Antoinette up that hill to pick dandelions for salads.

|

| Flora Severini, First Communion |

But within a few years from their move to Stone Street, there would be new challenges arising from events and forces far beyond Greensburg. After the New York stock market crash in the fall of 1929, the American economy began to weaken until by 1931 President Herbert Hoover was talking about “a great depression” taking hold. When corporations lost stock value they invested less, stopped expanding and eventually cut production. Families cut their spending, to ride out the temporary downturn. But it only kept getting worse. Banks failed (over 5,000 of them by 1932) so people lost their savings, and businesses could not get loans. People lost their jobs. Businesses closed. Some people lost their homes, and some went hungry.

|

| Johnstown 1934 |

Every kind of job was hit. One of the first was construction, which dropped nearly a third in 1930, and nearly another third in 1931. Manufacturing was not far behind: US Steel cut wages in September 1931, and cut them again in the spring of 1932. Between 1927 and 1933, Pennsylvania lost 270,000 manufacturing jobs.

Westmoreland County had a diversified economy, but parts of it were troubled even before the Depression took hold. Coal and coke production had been declining in the 1920s, so a combination of played-out mines, resistance to unions and then a drop in demand in the 1930s saw 40% of the remaining mines close.

Much of Westmoreland County was farm country, and that included Hempfield Township, which completely surrounded Greensburg. But farm income generally had been falling for years. The Depression made it worse. There was plenty of food, and no money to buy it. Farmers couldn’t sell overseas—there was Depression in Europe, too, and by 1931 the European banking system had collapsed.

|

| Unemployment line Pittsburgh 1933 |

Those with the least income—and the last workers hired, like the black steelworkers of Pittsburgh—suffered first, and worst. But the middle class was not exempt: across the US, teachers, nurses, ministers, engineers and middle managers were among those sleeping in parks, or living in tents with their families.

A million men were jumping onto to trains, piling into boxcars, and riding the rails back and forth across the country in permanent transit.People were desperate, and some did desperate things, adding to the sense of a world spinning out of control. There were many instances of people organizing to fight back, regardless of legality. Farmers in every part of the country stopped bank auctions of their neighbors’ farm equipment. In the Allegheny County borough of Rankin, members of the Unemployed Council halted a sheriff’s sale of the furniture of an unemployed man and his daughter by disarming a police officer, keeping out bidders while they themselves bought all the furniture for a total of 24 cents, and then returned it to the owner. In Wilkinsburg, adjacent to Pittsburgh, another Unemployed Council seized a Duquesne Light truck to prevent it from shutting off power to an apartment building.

1932 is considered one of the worst years of the Great Depression, if not the very worst. So it was not an ideal time to be starting a business. Yet it is likely that 1932 was the year in which Ignazio Severini started his.

It is true however that the Depression also provided opportunities. Such an opportunity arose for Ignazio when, in nearby Youngwood, the town’s only tailor went out of business.

|

| Gioconda Severini |

In the early 1930s, Domenick was moving his barber shop from his home at 207 Depot Street in Youngwood, to a building he bought in the middle of the next block at 313 Depot Street. There was room in the building on the ground floor for a tailor shop as well. Domenick would even give Ignazio free rent for awhile.

The Sons of Columbus had established their A & B Club in Youngwood as both a social club and a mutual support (the initials stood for either Americanization and Beneficial or Association and Beneficial, depending on who you asked.) Domenick suggested that they would probably provide Ignazio with a loan to buy the equipment the previous tailor left behind. The price would likely be low.

Youngwood was a much smaller place than Greensburg, just six miles away. Only about 3,000 people lived there, while 16,000 or so lived in Greensburg. But still, Youngwood needed a tailor, and Italians in nearby places might be attracted to a tailor who speaks their home language.

At that time Ignazio may have lost his job in Greensburg when the tailor shop closed, partly because the owner died. Though the 1930 Census confirms that in that year he owned their home on Stone Street, he subsequently may have lost that as well.

G. recalled that he was riding streetcars to McKeesport to work in a tailor shop there. But at least he was working, so starting his own shop would be taking a risk. Ignazio talked it over with G. They’d always planned that he would have his own tailor shop, and here it was.

There is a photograph of Ignazio in his shop published in Youngwood many years later that dates the photo at 1929. This so far is the only evidence that he’d opened the shop by then, and there is more evidence to the contrary. According to the U.S. Census, Ignazio was a tailor working as a “wage or salary worker” in 1930 rather than self-employed or a business owner. That suggests he hadn’t opened his shop yet, especially since his 1940 Census form said that by then he was “working on his own account,” which was Census code for self-employed.The more plausible date for the opening of the Severini tailor shop in Youngwood is 1932 (give or take a year), since according to Domenick’s daughter, her father opened his new barber shop in that building in 1932.

It’s not a quibble, because the difference is that most of 1929 was before the Depression, but 1932 was in the thick of it, and Ignazio was taking a bigger chance. In any case, he was certainly in business during the worst years of the Depression.

One important event in the Severini family definitely took place that year of 1932: the birth of Ignazio and G.’s son Carl on January 27. He was their third and last child.

A few important national events in 1932 might also be mentioned. That spring, thousands of American World War I veterans gathered in Washington, D.C. to petition Congress to pay them now the war bonus they’d been promised for 1945, because they were in desperate straits. They remained there in makeshift encampments, many with their families, through the summer. The press covered the story extensively, dubbing them the Bonus Army. This may have attracted Ignazio’s attention. As a World War I veteran himself, he may have been interested in the fate of his American counterparts.

Things were at an impasse in late July, with Congress failing to provide the bonus and with President Hoover opposed to it. It was then that a police officer trying to clear away a crowd from the entrance to the Treasury Department panicked and shot a veteran dead. Hoover called out the Army to settle things down. Instead, General Douglas MacArthur decided to make war on the Bonus Army.

MacArthur, with his officers including Major Dwight D. Eisenhower and Major George Patton, deployed tanks and tear gas, routing the veterans and burning down their camps with gasoline. Patton led a cavalry charge with drawn sabers against unarmed men, women and children. In a deadly irony pointed out by historian William Manchester, among those that Patton’s attack routed was a World War I veteran decorated for saving the life of Patton himself. Though newspaper stories of the day tended to support the government line that the Army had thwarted dangerous criminals and radicals, Hoover never recovered his political reputation.After the rout, the Army rounded up Bonus Army participants and their families, put them into trucks and drove them west on the Lincoln Highway, Route 30, with an undetermined destination. But the Mayor of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, offered the marchers a park where they could set up a new encampment. So just beyond Jennerstown, where Route 30 climbs steeply up Laurel Hill and trucks slowed in low gear, hundreds jumped off the back of the trucks. Many made their way to Johnstown, while others presumably straggled into Ligonier and Latrobe and other western Pennsylvania towns. Those who remained on the trucks would pass through Greensburg (where there was more opportunity to jump off) on the way to Ohio and points west.

Also in 1932, the baby boy of aviators Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh was kidnapped from his crib in an upper floor of their estate. A ransom note was found, a ransom was paid, but two months after the kidnapping, the boy’s body was discovered. The story was covered extensively in newspapers and magazines and on radio. With her own infant son asleep in his crib, this may have attracted G’s attention. But for certain, among those who followed it avidly was 12 year old Flora Severini, who never forgot it.

Then in November came the historic 1932 presidential election, with President Hoover the Republican candidate for re-election, and New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt the Democratic candidate. In local elections, newly naturalized Italians often voted with the ruling majority of their time and place, or for the candidates supported by their employers (usually Republican), because (as was often the case in the coal patches) their jobs might depend on it.In presidential elections, Italians had generally supported the Republican candidate until things began to change in 1928, when the Democrats ran Al Smith, the first Catholic to be nominated by a major party. His campaign was met in Oklahoma by the anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan. But among primarily Catholic Italians that 1928 candidacy began their move to the Democrats that became a majority in 1932 for FDR. Nevertheless, when FDR won the presidency in a landslide in 1932, Pennsylvania was one of only six states he didn’t win.

President Roosevelt took office in March 1933. By the end of the year the new administration made many changes. Price supports began improving farmers’ incomes. Rules for businesses and industries, a minimum wage and protections for workers (including a ban on child labor) were increasing profitability and incomes. The federal government started projects to get electrical power to rural areas.

The government supported relief efforts in all the states and began public works on what today is called infrastructure. An early example was probably the Greensburg Post Office building on Pennsylvania Avenue, erected in 1911, which was essentially doubled in size and modernized in 1934-5. It later become the Greensburg-Hempfield Public Library.Also by the end of the year the federal government increased confidence in the banking system by guaranteeing deposits for the first time. Even by the spring the banking system was stabilized and working again while the country began moving away from the gold standard (I recall G. telling me that when the government called in the last gold dollars, Ignazio kept a few as souvenirs. To my knowledge, they never turned up. But I do remember that for gifts he often gave silver dollars.)

So by the end of 1933, even though the Depression still gripped the nation, things were looking up. But there were other changes as well. The growth from immigration that had characterized Italian communities in the U.S. since the late 19th century came to a dead stop in the 1930s. The ships carrying thousands of Italians no longer sailed. In fact, more people were leaving the U.S. than entering it. That included Italians who returned home, where the money they earned in the U.S. would go farther, and family and social structures were better adapted to making do.

But those who stayed were establishing themselves and their children in their communities. Still, the support within the Italian community remained important, as did organizations like the A&B Society in Youngwood.

According to G., for awhile after he’d opened his shop, Ignazio Severini supplemented his earnings by taking several streetcars into Pittsburgh a few days a week to do tailoring work there. Otherwise, he was commuting by streetcar from Greensburg to his shop in Youngwood. G. remembered meeting him at the streetcar stop at 5:30 each day, with her baby Carl in her arms, or later, holding his hand beside her. They were followed both ways by their cat.But Ignazio worried about the snowy mornings when the streetcar tracks might be blocked and he couldn’t get to the shop. Soon he began to look around for a place for them to live in Youngwood. G. didn’t want to leave Greensburg but finally agreed when a house became available a short block from the tailor shop, across the street from the Gelfo residence. It was available because the store on the first floor facing the street had gone out of business. (This may or may not have been Jake Rueben's fruit market, which according to what Angeline Gelfo Miller remembered, was on this block but closed during the Depression.) The owner agreed to rent the house to them for $10 a month.

Perhaps after a brief return to living with Ignazio’s sister’s family in their house on Hamilton Avenue (which had since been expanded), the Severini family moved in 1933 or 1934 for the last time, to 200 Depot Street in Youngwood.